Exploring the Intricacies of Human Skull Anatomy and Its Clinical Relevance in Neuroanatomy and Surgery

- hanatomy16

- Apr 25

- 5 min read

The human skull is not just a protective shell for the brain; it's a remarkable structure that plays vital roles in our sensory experiences and physical functions. For medical professionals, especially those focusing on neuroanatomy and surgery, a deep understanding of skull anatomy is essential. This article will explore the detailed anatomy of the human skull, emphasizing its significance in clinical and surgical contexts.

Overview of Skull Anatomy

The human skull consists of 22 bones categorized into two main groups: the cranium and the facial bones. The cranium, composed of eight bones, is designed to safeguard the brain, while the facial skeleton, made up of 14 bones, shapes our facial features.

The cranial bones include:

Frontal Bone: Creates the forehead and the upper section of the eye sockets.

Parietal Bones: Two bones located on the sides and roof of the skull.

Temporal Bones: Positioned near the skull's base and house structures for both the inner and middle ear.

Occipital Bone: Forms the posterior and inferior part of the skull.

Sphenoid Bone: A butterfly-shaped bone that makes up part of the skull's base and the eye socket.

Ethmoid Bone: Contributes to the medial walls of the eye sockets and the nasal cavity.

The facial bones include key structures such as the maxilla (upper jaw), mandible (lower jaw), nasal bones (bridge of the nose), and zygomatic bones (cheekbones). Each plays a crucial role in not just our appearance but also in critical functions like chewing and breathing.

Understanding these bones is fundamental. For instance, a fracture of the mandible can affect nutrition, resulting in nutritional deficiencies if not treated promptly.

Neuroanatomy of the Skull

Neuroanatomy explores the structure of the nervous system, directly connected to skull anatomy. The skull encases the brain, which is essential for various bodily functions.

The brain is divided into three primary sections:

Cerebrum: The largest part responsible for cognitive functions like thinking, memory, and voluntary movement.

Cerebellum: Located beneath the cerebrum, it coordinates movement and balance.

Brainstem: Comprising the midbrain, pons, and medulla oblongata, it oversees vital functions such as breathing and heart rate.

Understanding the cranial fossa—depressions at the base of the skull—is crucial for diagnosing conditions. For example, brain swelling can change the position of these structures, leading to increased intracranial pressure, which can be immediately life-threatening.

Vasculature of the Skull

The skull's blood supply is vital for brain function. Major arteries, such as the internal carotid and vertebral arteries, deliver oxygen-rich blood, while the internal jugular veins mainly handle venous drainage.

Key vascular structures include:

Internal Carotid Arteries: Supply blood to the brain's anterior and middle sections, affecting around 80% of blood flow.

Vertebral Arteries: Supply the brain's posterior regions through the basilar artery, serving areas crucial for coordination and balance.

Understanding skull vasculature is crucial in situations like strokes, where occlusion of these blood vessels can lead to significant brain damage. Statistics show that nearly 795,000 people in the U.S. have a stroke each year, making knowledge in this area vital for timely intervention.

Surface Markings of the Skull

Surface markings on the skull serve as important landmarks clinically and anatomically. Identifying these bony landmarks can indicate underlying structures and potential health issues.

Important surface markings include:

Nasion: The bridge of the nose at the intersection of the frontal and nasal bones.

Bregma: The junction of the frontal and parietal bones, significant in assessing skull growth in children.

Lambda: Where the parietal and occipital bones converge, useful in growth measurement.

Mastoid Process: An extension of the temporal bone that serves as a muscle attachment point and is essential in managing infections.

These landmarks are invaluable during surgeries and in diagnosing conditions. For example, precise identification of the bregma during pediatric assessments can reveal issues in cranial development.

Clinical Applications of Skull Anatomy

Understanding skull anatomy has wide-ranging clinical implications. In neurosurgery, surgeons must navigate around delicate brain regions. Surgical techniques vary with procedures depending on cases like tumor removals or treating severe head injuries.

Key surgical considerations include:

Craniotomy: This procedure involves removing a section of the skull to access the brain. Preoperative imaging plays a critical role in selecting a safe approach.

Trauma Management: In incidents involving skull fractures, knowledge of the skull anatomy is crucial for minimizing brain injury and assessing vascular damage effectively.

For instance, a study showed that 30% of patients with severe head trauma also had vascular injuries that could complicate their recovery without proper understanding and intervention.

Neuroanatomy in Clinical Practice

Neuroanatomy is essential for understanding how the nervous system impacts overall health. This insight is crucial for diagnosing and treating neurological conditions.

Conditions often requiring neuroanatomical knowledge include:

Stroke: Understanding brain blood supply directs treatment decisions, such as whether to use thrombolytics based on the affected region.

Brain Tumors: Neuroanatomy guides the surgical approach, considering tumor location and associated risks, with some locations posing higher risks for critical functions.

Epilepsy: Identifying brain regions involved in seizures is vital for both medication management and surgical interventions.

For example, treating a patient with epilepsy may involve targeted surgery to remove a small section of the temporal lobe, which can reduce seizure frequency for nearly 70% of patients.

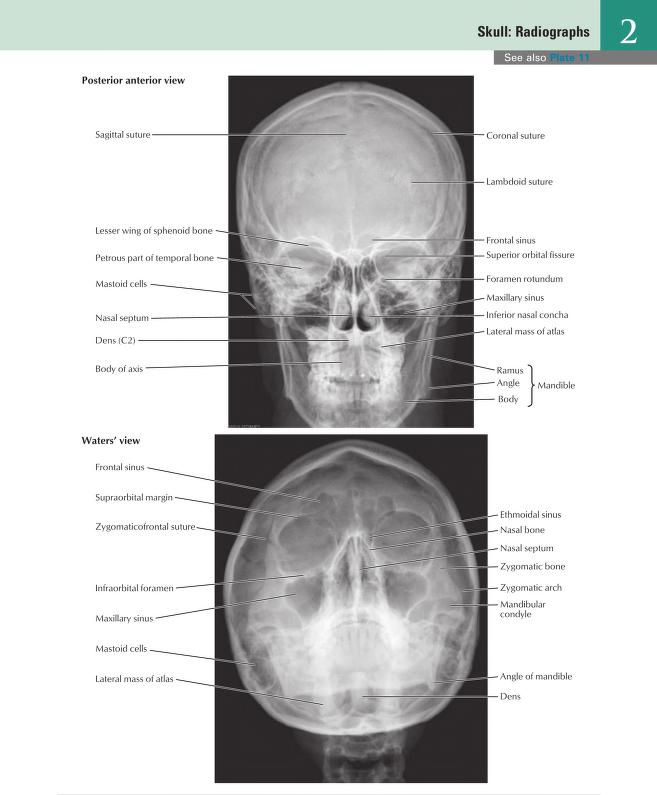

Advanced Imaging Techniques and Their Relevance to Skull Anatomy

Modern imaging technologies like MRI and CT scans have transformed skull and neuroanatomy assessment. These techniques allow for non-invasive views of the skull and underlying structures.

Key imaging advancements include:

MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging): Provides high-resolution images of soft tissues, including the brain and blood vessels, without radiation exposure.

CT (Computed Tomography): Critical in trauma situations, CT provides rapid images, making it pivotal for identifying skull fractures and bleeding.

These imaging tools significantly influence diagnoses and treatment plans. For instance, timely CT scans can change outcomes in 60% of trauma cases by quickly revealing life-threatening conditions.

Insights into Skull Anatomy and Its Impact on Medicine

Understanding the human skull anatomy is not just an academic exercise. It carries profound implications for medical practice, especially in surgery and neurology. A firm grasp of skull structure, neuroanatomy, and vascular systems enhances the ability to diagnose and treat various conditions effectively.

Knowledge of skull anatomy enriches the clinical approach to patient care. For medical students and professionals, mastering these concepts is a crucial step toward excellence in practice, ultimately leading to better outcomes for patients across diverse medical fields.

A solid understanding of skull anatomy forms a vital foundation for anyone in the medical field, setting the stage for success in neurology, surgery, and emergency medicine.

Comments